Whitewash Village: Chatham’s Lost Atlantis

Share

Cape Cod is no stranger to shifting landscapes and lost history, but few stories are as compelling as that of Whitewash Village, a once-thriving fishing community that now mostly lies beneath the waves. Known as Chatham’s own Atlantis, Whitewash Village—also called the Village at Monomoy Point—was a bustling maritime hub before nature reclaimed it in the 19th century. Today, only fragments of wood and brick foundations remain, occasionally peeking out at low tide.

The Treacherous Waters of Monomoy

Long before Whitewash Village was established, Monomoy was known for its treacherous waters and shifting shoals that posed a serious threat to mariners. Indigenous people once guided ships safely past Pollock Rip, Stonehouse, and Little Round Shoals, preventing them from running aground. In 1606, Samuel de Champlain referred to the area as Cape Batturier (meaning "the Cape where rocks are near the surface") after being forced ashore due to a broken rudder, while other French explorers called it Cape Malabar—"Cape of Evil Bars." Even the Pilgrims, deterred by the forbidding Pollock Rip Shoal, turned the Mayflower back toward Provincetown instead of venturing further south.

The Rise of Whitewash Village

The first recorded human activity at Monomoy Point dates back to 1711 with the establishment of Stewart’s Tavern at Wreck Cove, providing shelter and sustenance to sailors navigating the treacherous waters off Cape Cod. Starting in the late 1600s, the cove was used for trading molasses and rum from the West Indies. By the early 19th century, the deep natural harbor known as the Powder Hole attracted a thriving fishing community, with nearly 200 residents calling the area home.

The village’s economy revolved around cod, mackerel, and lobster, which were abundant in Nantucket Sound. Lobsters, then considered a poor man’s food, sold for just a couple of cents each. Whitewash Village also became a supply hub for fishing fleets, featuring shipyards, chandlers, and general stores. The village’s simple, whitewashed buildings gave rise to its evocative name.

At its peak, Whitewash Village had a school—Public School #13—serving local children, a wharf, and a lively inn and tavern called the Monomoit House. The tavern was a favorite haunt for sailors, traders, and fishermen, many of whom sought refuge from the area’s infamous shipwrecks. The Monomoit House was known as an "amphibious structure" because at high tides, the water would be up to the front stairs.

Monomoy Point Lighthouse: A Beacon in the Fog

Recognizing the dangers of Monomoy’s shifting shoals, the Monomoy Point Lighthouse was established in 1823 to guide sailors through these treacherous waters. The original light was a wooden tower with a brick lantern room atop the keeper’s house. In 1849, a new tower—one of the first cast iron lighthouses in the United States—was constructed. The lighthouse station included a two-story keeper’s house, a light tower sheathed in cast iron, and an adjacent generator house.

"Lighthouse at Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge" by U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service - Northeast Region is marked with Public Domain Mark 1.0.

Giddings Ballou: The Artist, Teacher, and Historian

One of the most notable figures of Whitewash Village’s history was Giddings Ballou, who not only served as the schoolmaster but also captured the essence of village life through his artwork and writings. Ballou was a skilled portrait artist, and his illustrations of Whitewash Village, published in Harper’s Monthly Magazine in 1864, remain some of the best visual records of the community. His sketches depicted the daily struggles and triumphs of the villagers, from fishermen at work to shipwreck survivors warming by the stove at Monomoit House.

Some of Ballou's artwork can be viewed at the Atwood Museum. Online files can be found at https://chatham.catalogaccess.com/people/50030

A Life at the Mercy of the Sea

The waters around Monomoy were notorious for shipwrecks, earning the area the ominous nickname The Land of the Evil Bars. Many villagers played the dual role of lifesavers and wreckers—rescuing stranded sailors while salvaging valuables from doomed vessels. Some were even rumored to have lured ships to their demise to profit from the wreckage.

Despite its hardships, life in Whitewash Village thrived for decades. The village school held four terms a year, and local teachers—often the wives of fishermen—kept the community’s children educated. However, in December 1859, Ballou wrote a plea to the town selectmen for an outhouse, humorously emphasizing the remote hardships of the island settlement.

The Great Storm and the Village’s Fall

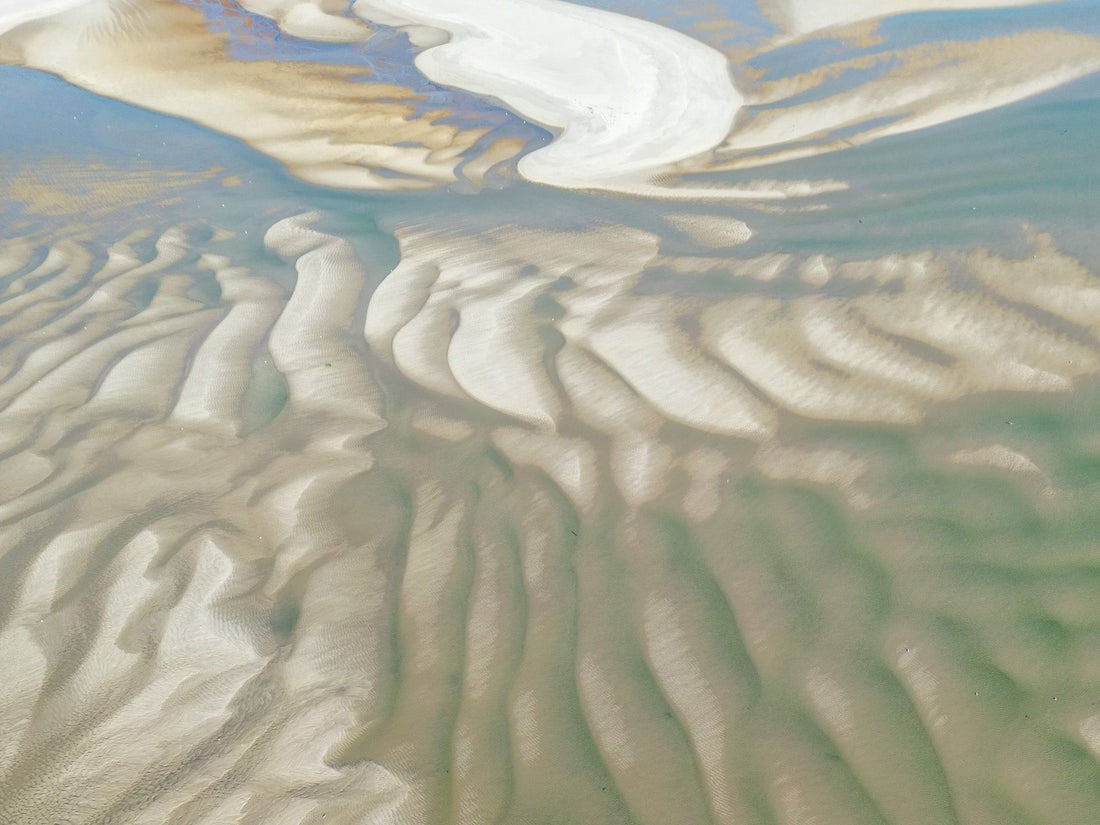

In 1860, a powerful winter storm changed everything. The storm reshaped the coastline, sweeping away the northwest point and filling in the Powder Hole harbor with sand. The once-protected anchorage became too shallow for vessels, driving the fish away and crippling the community’s economy. Without a steady livelihood, the villagers abandoned Whitewash Village, with some even floating their homes to the mainland for relocation.

By the early 20th century, Monomoy’s ever-changing geography further fragmented the island. Today, the village site lies underwater, with only the Monomoy Point Light and a few scattered remnants as reminders of its once-thriving existence. The lighthouse, decommissioned nearly a century ago, stands as a silent witness to the village’s lost glory.

Visiting Monomoy Today

Though no permanent structures remain from Whitewash Village, Monomoy Island is still a place of intrigue and natural beauty. Since 1944, it has been a protected wildlife refuge managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, providing a sanctuary for migratory birds, harbor seals, and gray seals.

For adventurous visitors, boat charters offer a chance to explore Monomoy’s shores. One of the best ways to get close to the historic site of Whitewash Village is through Monomoy Island Excursions, a family-owned tour company with over a decade of experience guiding visitors through the area’s rich history and wildlife.

Whitewash Village may have vanished beneath the waves, but its legacy endures in the stories passed down through generations. For those willing to seek it, Chatham’s lost Atlantis still whispers its tales through the shifting sands and the rolling tides of Cape Cod.